Although efforts have been made to define community in many disciplines, there is yet to be a clear conceptualization of the construct. This lack of coherence has been evident since 1955 when sociologist George Hillery compiled over 90 definitions of community and found the only commonality across all these sources to be that they dealt with people (p111).

Early online sociologists also struggled with the term. Jonassen et al. (1998) state that community can be defined as a social organization of people who share knowledge, values and goals. Group members come to depend upon each other for the accomplishment of certain goals or to fulfil certain roles. Social groups become communities when the interaction and consistent communication between group members lasts long enough to form a set of habits and conventions, which allows symbolic interactionism to be used to study them (Wilson and Ryder, 1996).

With the rise of new media, however, online communities have challenged the concept of traditional communities. Communities no longer exist only in the physical world but also in the virtual world that operates through the internet, or, as Fernback states, we can ‘leave behind bodies, prejudices and limitations associated with those bodies, to interact solely as minds in an unfettered environment’ (2007, p51). Community can be prescriptive, descriptive and normalising in a way that is perhaps best usurped by the study of social relations, as a geographic place has been replaced by a sense of collectivity (Janowski 2002, p39).

The term ‘glocalized’ has been invented to describe internet-based communities which can have global and local connections, such as the one I’m studying, where ‘‘worldwide connectivity and domestic matters intersect’’ (Wellman & Gulia, 1999, p. 187). Self-help groups in which users interact with each other, gather information and learn about local treatments and support demonstrates glocalization well (Riper et al 2008, p218; Lieberman and Goldstein 2005, p855). Thus, online communities seem to have many of the characteristics of offline communities. As Fernback (1999) summarizes, ‘‘cybercommunities are characterized by common value systems, norms, rules, and the sense of identity, commitment, and association that also characterize various physical communities and other communities of interest’’ (p. 211).

A pertinent local example of this type of community is Mess and Noise (M+N). M+N is predominantly used to share information and opinions about music, especially local music and current issues. Discussions extend to politics, popular cultural phenomenon, personal issues and irreverent humour. The site is moderated but interaction from the moderator occurs rarely and few users have ever been banned or discussion threads removed even when discussion rules have been broken.

Using the concepts of symbolic interactionism and role theory I chose to analyse the styles of interaction, the reasons people use the site, and the values placed in it.

In her study of online fandom, Baym states that there is a generation of collective intelligence and affect with the creation of self concepts and self presentations within fan groups prior to the creation of a shared identity (Baym 2007, p2). As with many sites, M+N asks contributors to adopt an identity (usually anonymous) to share the knowledge that is essential to the survival and success of their online communities. Anonymity has been shown to increase antisocial comments in online communities and the popularity of adopting a (usually culturally referential) username has been shown to markedly increase user participation, while peripheral participation has been shown to remain unaffected (Kilner and Hoadley 2005, p272).

The common approach of symbolic interactionism when analyzing communities bypasses two of its main contributing qualities, location and organisation. Through its focus on meaning and identity, interactionism can help to understand the reasons people choose to be part of this community, regularly contribute to it and often find it hard to leave. There is a high level of group cohesion, which is critical to the flourishing of any community, and a high level of ‘lurkers’ or ‘social loafers’; people who follow discussions but contribute little or nothing (Shiue, Chiu and Chang 2010, p768).

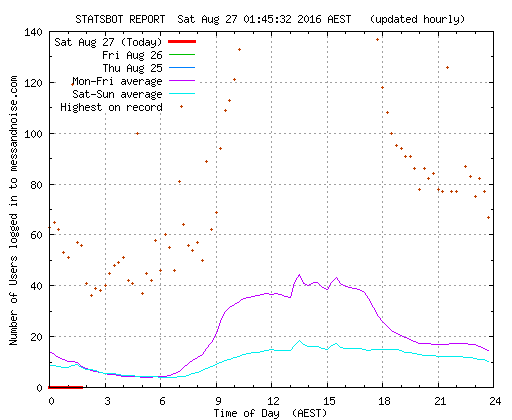

Many users on M+N are friends outside of the community given that the majority of users live in Melbourne. Anonymity is not as pronounced here as in other more subject-specific forums. Though gender can be hard to determine, gender split is relatively equal. Typically there are around 20-50 people using the site at any one time during the day, meaning that the interactivity of a community is constantly occurring (Figure 1. p3)

Symbolic Interactionism and Online Communities

Symbolic interactionism (SI) was outlined by sociologist Herbert Blumer in 1969, Blumer set out three basic premises of the perspective:

- "Humans act toward things on the basis of the meanings they ascribe to those things."

- "The meaning of such things is derived from, or arises out of, the social interaction that one has with others and the society."

- "These meanings are handled in, and modified through, an interpretative process used by the person in dealing with the things he/she encounters." (Blumer 1969)

To examine the meanings people find in things is to focus on micro-level interactions. Theoretically, these can be used to extrapolate meaning in behaviour and knowledge gained about a community or society from that. In sourcing knowledge of an individual, SI examines the individual’s relationship with their environment, or in this case, the relationship to and within an online community.

As an example in this context, the exchange documented in Appendix I (p9) can be used to examine meaning found in participating in M+N; participant observation is a useful tool for gathering information when using SI making this an ideal method for online community analysis.

In this case we can see that users are discussing the relationship between income and happiness. The perspective adopted indicates that contributors to this discussion appear to be literate, aspirational, of low to median income, relatively articulate, respectful of others comments and use humour as a way to deflect from the seriousness of the issue.

In keeping with the principals of SI, there is a high degree of interpretation of other users’ actions rather than a straight response to them. There are jokes, abbreviations, cultural references, frequent references to local people, places and bands and customization of language and tone in keeping with the known dialogue of the community. This is an example of a community using symbols and signification and meaning can be found within one another’s actions.

Symbolic communication is an important and defining device when using SI to construct a reality. SI states that material and individual realities are constructed through a communicative and dynamic process. Blumer’s (1969) interpretation of SI posits that humans act toward social stimuli based on meanings they hold about those stimuli. These meanings are generated and developed through social interaction, and people’s interpretations mediate their understandings of their culture (Blumer, 1969; Musolf, 2003). Thus, human agency or our ability to construct meanings and act upon these meanings define and build the SI study of community. Cohen’s (1985) focus on symbolic meaning as defining community reflects this interactionist perspective. The Chicago school in which Mead developed and SI grew conceived the self and social elements combining to result in human action and believed meaning construction occurred through symbolic interpretation as a way to build communities with shared interests (Kreiling and Sims 1981, p15).

Strauss’s study of interaction focuses on the definition of boundaries of social worlds. He explores Shibutani’s ideas of boundaries as set by the ‘limits of effective communication’ (1978, p119). This theory can be applied to M+N as many may visit the site but few will be informed enough to understand the references to habits of members, or many may be put off by the initial cynical, obscene or negative tone of many threads. This limits the growth of the site to those who have the requisite patience or knowledge of popular and local culture.

This boundary-setting elitism or focus on a user with a certain style of interaction is one way of regulating the size and style of the community.

Online Communities, Boundaries and Social Capital

In Lee and Lee’s article the authors explore the positive relationship between online community use and social capital (2010, p712). They argue a site like M+N supports face-to-face interactions, that its users have a higher level of sociability than non-users and that communication abilities are enhanced through technological advances. SI and social capital are complementary as the value in social capital can be easy to ascertain. A community desires social capital and the information held within a site like M+N can be seen to be capital. The discussion in Appendix II indicates an example of M+N community organising a community rally to protest against the closure of a live music venue, and the lack of support for a similar venue in Sydney. This supports Lee and Lee’s suggestion of the value placed in real world interaction.

This sentiment is also reinforced in Baym’s article. She argues that there may be a shared ethos but disagreements are common and actually desirable as there is a high level of creativity which is promoted and enabled in new ways by the use of the internet (2007, p2). Baym also suggests that a sense of community may be formed by the users on one site meeting again on another site which aims to unite people with a more specific interest, mimicking the ‘bumping into someone’ manner of meeting in geographically place-based communities (Baym 2007, p13). It could also be argued that a community cannot be understood by referring to one site alone, particularly when a specialised interest is shared.

How SI has Influenced My View of M+N

Having been an occasional contributor to M+N for three years I found a forced external view interesting, and questioning why the community exists and reasons for its popularity. Educated people who have access to the internet and opinions about art and music abound in Melbourne and when given an opportunity to argue from a relatively anonymous position, will be attracted to that. As a place for learning about what is currently popular, younger people will go there to find out and older people will dispense what they perceive as wisdom. Both give the site value and user become invested in their identities over time. M+N sees a commitment to the community from many of its members with a suicide and several near suicides of members bringing face-to-face help from others who had not previously met. Symbolic communication can be regarded as purposeful social action in keeping with Blumer’s theory; however people cannot be active in a community without contiguity meaning that a geographical closeness is needed to allow this to happen. Neither can it be regarded as a substitute for offline socialisation.

There is likely to be a great deal more research on the application of social community theory to online communities. Though symbolic interactionism is a useful way to analyse online communities and the interaction therein, there is likely to be a surge in new sociological approaches which combine current disciplines in order to understand the relationships herein in an academic, legal, political and economic sense. Online communities are increasing in number and in importance as recognised by the amount spent on advertising in online communities and the opportunities they represent for socialisation and targeted marketing (Papworth, 2010). Around ten of the top fifty most popular websites are social networking/online community websites ("

http://www.mostpopularwebsites.com";

www.mostpopularwebsites.com; "

http://www.alexa.com/topsites"; "

http://www.google.com/adplanner/static/top1000/"). One could argue that the term community needs to be modified as there is a convenient togetherness on online communities but no real responsibility is engendered and, in fact the placement of social groups with ‘egocentric networks’ can be found to be true in some places (Boyd 2006, p12). Ultimately it matters more how well we understand it rather than what we call it. SI is a useful, if limited, tool for increasing our information about online interactions.

- Atkinson, P. Housley, W. (2003) Interactionism Sage Publications, London, UK

- Baym, N. (2007) The new shape of online community: the example of Swedish independent music fandom First Monday 12:8;1-17

- Blumer, H. (1962) Human behavior and Social Processes Routledge & Kegan Paul, London, UK, 179-

- Blumer, H. (1969) Symbolic Interactionism: Perspective and Method University of California Press, Berkley USA

- Boyd, D. (2006) Friends, Friendsters and Fop 8: Writing community into being on social network sites First Monday 11:12;1-12

- Clarke, A. (1991) Social Worlds/Arenas theory as organisational theory Social Organisation and Social Process: Essays in honor of Anselm Strauss Aldine de Gruyter Publishers, New York, USA p119-140

- Cohen, A. (1985) The Symbolic Construction of Community Ellis Horwood Publishers, Chichester, UK

- Fernback, J. (1999) There is a there there: Notes towards a definition of cybercommunity in Doing Internet research: Critical issues and methods for examining the Net Jones, S. Ed. Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks USA pp203-220

- Fernback, J. (2007) Beyond the diluted community concept: a symbolic interactionist perspective on online social relations New Media & Society 1:49-69

- Forte, J. (2001) Theories for Practice: Symbolic Interactionist Translations University Press of America Lanham, USA

- Jankowski, N. (2002) Creating community with media: History, theories and scientific investigation in The Handbook of New Media Lievrouw, and Livingstone Eds. Sage Publishing, London, UK p34-49

- Jenkins, H. (2006) Convergence culture: Where new and old media collide New York University Press, New York, USA

- Jonassen, D. Peck, K. Wilson, B. (1999) Creating Technology-supported Learning Communities in Learning with Technology: A constructivist perspective Prentice Hall, Upper Saddle River, USA

- Hillery, G. (1955) Definitions of Community: Areas of Agreement Rural Sociology 20:2;111-123

- Kreiling, A. Simms, N. (1981) Symbolic interactionism, progressive thought and Chicago journalism in Foundations for Communication Studies Soloski, J. Ed. Center for Communication Study, University of Iowa, Iowa City USA pp5-37

- Lee, J. Lee, H. (2010) The computer-mediated communication network: exploring the linkage between the online community and social capital New Media and Society 12:5;711-727

- Lieberman, M. Goldstein, B. (2005) Self-help online: An outcome evaluation of breast cancer bulletin boards Journal of Health Psychology 10:855-862

- MostPopularWebsites "http://www.mostpopularwebsites.net" Accessed 7th September 2010

- Musolf, G. (2003) ‘The Chicago School’ in Handbook of Symbolic Interactionism Reynolds, L. And Herman-Kinney, N. Eds. AltaMira Publishers, Walnut Creek, USA pp91-117

- Papworth, L. (2010) Monetization: Social Network Advertising "http://laurelpapworth.com/social-media-monetization-social-network-advertising/"Accessed 7th September 2010

- Reich, S. (2010) Adolescents’ sense of community on Myspace and Facebook: A mixed-methods approach Journal of Community Psychology 38:6;688-705

- Riper, H. Kramer, J. Smit, F. Bonjin, B. Schippers, G. Cuijpers, P. (2008) Web-based self-help for problem drinkers: A pragmatic randomised trial Addiction 103:218-227

- Shiue, Y. Chiu, C. Chang, C. (2010) Exploring and mitigating social loafing in online communities Computers in Human Behaviour 264:768-777

- Strauss, A. (1978) Social Worlds Studies of Interaction 1:119-128

- The 1000 most-visited sites on the web "http://www.google.com/adplanner/static/top1000/" Accessed 7th September 2010

- Top Sites: The Top 500 Sites on the web "http://www.alexa.com/topsites Accessed 7th September 2010"

- Wellman, B. Gulia, M. (1999) Virtual communities as communities: net surfers don’t ride alone in Communities in Cyberspace Smith, M. Kollock, P. Eds. Routledge Publishers, New York, USA

- Wilson, B. Ryder, M. (1996) Dynamic Learning Communities: An Alternative to Designed Instruction Proceedings of Selected Research and Development National Convention of Association for Educational Research and Technology, Indianapolis USA < HYPERLINK "http://carbon.ucdenver.edu/~mryder/dlc.html"http://carbon.ucdenver.edu/~mryder/dlc.html> Accessed 6th September 2010